Lottie was the youngest child of Marcus and Abbey Angel. Marcus and Abbey were young parents, given the size of their family. Although Marcus was a full decade her senior, Abbey had been only 20 when their first boy, Michael, was born. By the time Lottie was born, Abbey was well into her thirties; but she still carried herself as a young parent, looking at Lottie with the awe of a first-time mother.

Lottie was the youngest child of Marcus and Abbey Angel. Marcus and Abbey were young parents, given the size of their family. Although Marcus was a full decade her senior, Abbey had been only 20 when their first boy, Michael, was born. By the time Lottie was born, Abbey was well into her thirties; but she still carried herself as a young parent, looking at Lottie with the awe of a first-time mother.

Although their four boys had grown up in the city, Marcus and Abbey decided to move to the quieter outskirts of town when Lottie was born. They found a log house on a large plot of flat land, where they didn’t have to worry about the boys playing in the street. There was even a barn on the property!

Marcus, a shrewd banker, quietly accepted the hour-long commute into town each day, which, compiled with his 9-hour work day and his after-work café habit, resulted in his spending less and less time at home each day, often arriving just after dinner, as Abbey was trying to convince the kids to wind down for the evening.

Never a very emotional man, Marcus withdrew from the kids a bit, never finding the time to connect with the newest addition to the family.

Abbey, a wild and eccentric painter, moved her work into the large family home, staying in with the kids and doing her best to keep painting as the boys ran wild on the property.

With nothing better to do in the new neighbourhood, Lottie’s brothers entertained each other by playing rough with little Lottie. She had hardly learned to stand before they were shoving her to the ground. She had only to walk across the room before one of them would pick her up and carry her back to where she had started.

Until Lottie grew too heavy and too feisty, her brothers would amuse themselves by playing Lottie-catch, or even, when she was tiny, Lottie-vertical-soccer (with a new, specially instated rule: hands only, no kicking!).

Lottie fit nicely into small spaces, like the crack behind the stove and the top shelf of the linen closet. She was a brooding, morose adversary, and, with the massive size of the house and her lack of vocal complaints, her brothers felt comfortable exploring the laws of physics with Lottie as the test-subject.

Too young to understand that her brothers’ teasing was a furtive expression of affection, Lottie nursed a secret hatred for her torturers. Her lower lip sliding outward in a sullen pout, she would daydream about growing big enough to force her brothers into narrow spaces, and toss them from hand to hand like dolls. Knowing that it was highly unlikely that she would ever be a giant, Lottie taught herself silent defences that could maintain the honor of the no-adults-involved justice system.

A steady kick in the stomach when they picked her up; the slow pressure of her thin fingernails into the skin of their arms. If she forced her brothers to shriek when she remained so quiet, surely she was the more powerful of the opponents.

The only brother Lottie allowed herself to forgive was Michael. Sometimes he could be nicer to her than the other boys, and even when he was mean, he would give her a tender smile with eyes that apologised sincerely. He would leave his room unlocked sometimes, allowing Lottie to play with his old toys or curl up in the hidden corner behind his bed.

Lottie began to seek out the small places she had once feared, discovering relief in a secret game of hide and seek. The back of the walk-in pantry. Her mother’s paint cabinet under the stairs. The old-fashioned toy chest her dad had inherited from his grandmother. The crawlspace that housed the water-heater. The attic that housed a ghost. The dusty hay-loft in the barn.

Lottie began to seek out the small places she had once feared, discovering relief in a secret game of hide and seek. The back of the walk-in pantry. Her mother’s paint cabinet under the stairs. The old-fashioned toy chest her dad had inherited from his grandmother. The crawlspace that housed the water-heater. The attic that housed a ghost. The dusty hay-loft in the barn.

Lottie memorized every creaking board and every crack in the wooden walls. She knew the pace that the house breathed, could feel the weight of her brothers in another room in the floor under her own feet. She learned the secret ways to open locked doors, the special ways to climb to places she couldn’t reach. She could move without a sound, knew to replace the door behind her as she snuck around.

She used to steal into her mother’s studio and watch her paint. Abbey’s big canvases were covered in thick, warm, bright colours that sang of a happiness Lottie learned to feel.

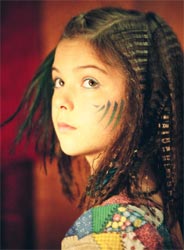

Lottie would watch her mom for hours as she flicked, pulled, and dripped paint across the canvas, sometimes accidentally dripping, flicking, and pulling paint across her own face and clothing. When she watched her mom work, she didn’t feel like she was hiding from the boys, or biding time until she was old enough to begin school, she felt like she was free–a grown up woman watching a ballet dancer move.

She never spoke to her mom much, but it was through her mother’s work, through the passion and the tenderness she betrayed as she painted, that Lottie learned to love.