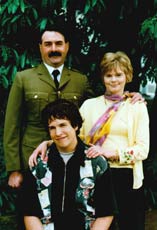

Ramone Kingsley was a hypochondriac. His mother blamed his father Lawrence for his military tidiness—early childhood conditioning, Sue claimed. You have fathered a boy who is afraid to make a mess.

Ramone Kingsley was a hypochondriac. His mother blamed his father Lawrence for his military tidiness—early childhood conditioning, Sue claimed. You have fathered a boy who is afraid to make a mess.

And so he had. Lawrence raised his boy in a shady suburban neighborhood that was host to dozens of other military families. Lawrence had chosen this neighborhood specifically for its strict housing ordinances, which forced his neighbors to maintain tidy yards and houses; water the flowers, trim the bush, skim the pool, hide the10-inch satellite dish.

He found the sound ordinances quite satisfying, liked knowing that his house, and every other house on the block, would be in complete order by 10, and that everyone would be in bed with the lights out by 11. It was calming, gave him a sense of control.

Ramone had inherited his father’s need for order and control, his love of the tidy, and disgust for the chaotic. He feared the world outside of his direct control, feared the random conversations with strangers on the street, the free-flying molecules in the uninhibited air.

He was afraid of cars that passed by as he lingered on the sidewalk, afraid that sweat would pour from his palms and drop him to his death if he ever played on a playground, afraid that he would catch a horrific disease if he didn’t hold his breath as he moved through a crowd.

Ramone was quite happy to stay inside of his father’s safe house during the day, pressing his face to the cool glass of his second-story window, letting the chill dampen his feverish thoughts, knowing that he was just out of reach and the world could not touch him.

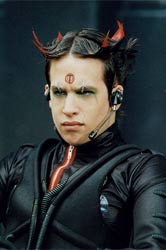

His father often let him sit out of school, coddling Sue with the claim that their boy would learn more at home than in the classroom. So little Ramo stayed in more often than not, playing on the high-tech toys his father snuck home from work, taking apart and reassembling computers and household items, rewiring; always rewiring.

He could spend days at a time scripting on a computer, would often upset his father by awakening after midnight, and typing away furiously in the night. But he could never help it. He was driven to the point of obsession.

It was the same urge that cause Lawrence to clip his fingernails until they blended smoothly into his fingertips. Until a project was wrapped up in complete working order, Ram could not eat, could not sleep, could not think without vile thoughts of failure and incompletion screaming though his head.

It was the same urge that cause Lawrence to clip his fingernails until they blended smoothly into his fingertips. Until a project was wrapped up in complete working order, Ram could not eat, could not sleep, could not think without vile thoughts of failure and incompletion screaming though his head.

Sometimes, Ram felt a certain, solid emptiness, a sureness that he was missing something. It was a feeling he felt most strongly when he was alone, when his father was off on a working sabbatical and his mother was working late to finish a project of her own.

In times like that, Ram would watch the shadows creep down the walls in the afternoon, and settle on the carpet, growing, filling the entire house with darkness. He would wait until he could not stand it anymore, and then he would flick on a switch with an exaggerated sense of satisfaction, pretending that all of his anxieties had been settled with the turning of a circuit.

Ram lived like a child in a bubble, nervously prowling and pacing through his home, his room, his staircase, checking doors and windows to assure that all exits were secured, that no one could get in or out, that the world could not touch him.

He imagined sometimes that he must have received HIV through a blood transfusion his parents forgot to mention, that he really could be plagued to his death merely by stepping outside, that he was a child made of glass and the air was poison.

It began to seem to him that he was held inside against his own desires, that he was detained for his own protection. He had spent so much time fearing his own mortal weaknesses that he had created a reality for himself that supported his own fears.

Even his mother unwillingly participated in this charade, never knowing how deeply her son had poisoned his own thoughts.